IRS Wage Garnishment Table: How much can the IRS Garnish?

August, 08 2022 by Steve Banner, EA, MBA

“Wage garnishment” is the term used to describe one of the methods the IRS can use to recover funds from taxpayers who have an outstanding tax debt. Taxpayers with a debt owed to the IRS have a number of options at their disposal to make payment arrangements, such as installment agreements or periodical payments – all of which will avoid the need for the IRS to take the step of levying the taxpayer’s property or wages.

However, those taxpayers who fail to take advantage of the alternative options may eventually find themselves in a wage garnishment situation. This process does not happen suddenly, and the taxpayer is given numerous warnings and opportunities over the course of several months to prevent the IRS from taking this extremely serious action. In this case, the taxpayer’s employer withholds a portion of the taxpayer’s salary and pays it directly to the IRS. The garnishment process usually begins with the IRS contacting the taxpayer’s employer and instructing them to take funds out of the taxpayer’s paycheck. The employer must send these funds to the IRS and, if it fails to do so, the employer itself may find itself liable with a tax debt of its own.

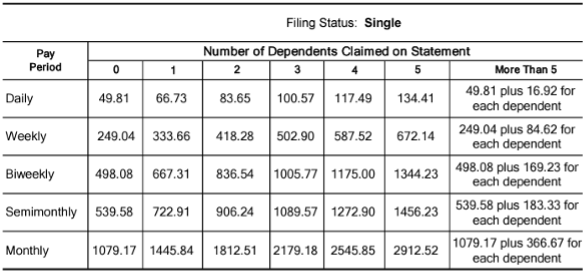

A taxpayer in this position may ask how much of each paycheck will be withheld for the garnishment. Although we might expect the amount withheld may be a modest proportion of the taxpayer’s salary that won’t affect his lifestyle too much, the opposite is the case. The IRS uses an annually updated table to determine how much the taxpayer needs to live on and then it takes the rest. The base amount left for each taxpayer is based on his filing status and number of dependents. IRS Publication 1494 sets the amounts that are exempt from garnishment.

The following excerpt from Publication 1494 for 2022 shows that a single taxpayer with no dependents who is paid weekly may be left with as little as $249.04 in his paycheck each week. The remainder of his salary, wages, commissions, and bonuses for the week will be sent to the IRS and used towards his tax debt.

If the taxpayer, in this example, had a second job, the IRS may garnish the entire amount of his paycheck from that job, provided that the taxpayer’s weekly living expenses were covered by his salary from his first job.

Once it has begun, the garnishment will stay in place until it is released by the IRS. This will take place when the taxpayer does one of the following:

- pays the tax bill in full,

- sets up a collection agreement,

- proves to the IRS that the garnishment is causing the taxpayer a financial hardship, or

- the period for collection of the taxpayer’s debt ends.

What we most often see is that taxpayers will end their wage garnishment by entering into an installment agreement to pay their debt monthly.

The clear lesson to be learned here is that prevention is better than cure. Why put yourself and your employer through the difficulties and embarrassment of having your wages garnished if you can avoid it? The much better approach is to set up an IRS collection agreement before the IRS ever takes your wages.

If you have a tax debt and are not sure how to proceed, or what options are available to you, our advice is to call one of our experienced tax professionals at TaxAudit for a cost-free and obligation-free assessment of your case. Our experienced tax professionals will help you figure out the best IRS tax debt settlement option for your situation.